Combating Covid-19

Home | COVID-19 | HIV/AIDS | ART | Research Team

English | Portuguese

Overview

We are supporting the fight against COVID-19 in Mozambique by collecting survey data and testing public health interventions over the phone.

We seek to support the Mozambican COVID-19 response, in collaboration with the government’s health research center for the central region, by following up on a study sample of a randomized controlled trial in Mozambique. Sample households will be contacted by phone and administered several rounds of surveys regarding COVID-19 knowledge, beliefs, and behavior. We will randomize novel over-the-phone interventions to test if we can encourage social distancing by accelerating changes in community norms and improve knowledge about COVID-19 via incentives and tailored feedback. Our findings will support the Mozambican response by informing policymakers of the public's COVID-19 knowledge and behaviors and on which public health messaging strategies are best to pursue given limited resources.

Publications

Correcting Perceived Social Distancing Norms to Combat COVID-19 (also available through the National Bureau of Economic Research)

-

Authors: James Allen IV, Arlete Mahumane, James Riddell IV, Tanya Rosenblat, Dean Yang, and Hang Yu

-

Abstract: Can informing people of high community support for social distancing encourage them to do more of it? We randomly assigned a treatment correcting individuals’ underestimates of community support for social distancing. In theory, informing people that more neighbors support social distancing than expected encourages free-riding and lowers the perceived benefits from social distancing. At the same time, the treatment induces people to revise their beliefs about the infectiousness of COVID-19 upwards; this perceived infectiousness effect as well as the norm adherence effect increase the perceived benefits from social distancing. We estimate impacts on social distancing, measured using a combination of self-reports and reports of others. While experts surveyed in advance expected the treatment to increase social distancing, we find that its average effect is close to zero and significantly lower than expert predictions. However, the treatment’s effect is heterogeneous, as predicted by theory: it decreases social distancing where current COVID-19 cases are low (where free-riding dominates), but increases it where cases are high (where the perceived-infectiousness effect dominates). These findings highlight that correcting misperceptions may have heterogeneous effects depending on disease prevalence.

- Keywords: COVID-19, Social Distancing, Health Behavior, Health Policy, Behavioral Economics

- JEL Classifications: I12 (health behavior), D91 (Micro-Based Behavioral Economics: Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making), O12 (Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development)

- Presentations: Johns Hopkins Special Online Conference on Experimental Insights from Behavioural Economics on Covid-19 | Human Capital, History, Demography, & Development (H2D2), University of Michigan

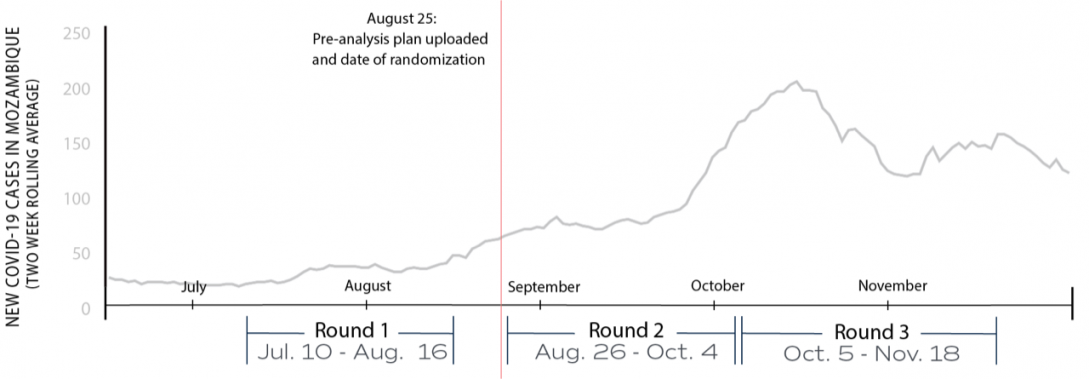

- Pre-Analysis Plan: submitted to the American Economic Association’s RCT Registry on August 25, 2020, under registration ID number AEARCTR-0005862.

- Populated Pre-Analysis Plan (Populated PAP)

Teaching and Incentives: Substitutes or Complements? (published in the Economics of Education Review and also available through the National Bureau of Economic Research)

-

Authors: James Allen IV, Arlete Mahumane, James Riddell IV, Tanya Rosenblat, Dean Yang, and Hang Yu

-

Abstract: Interventions to promote learning are often categorized into supply- and demand-side approaches. In a randomized experiment to promote learning about COVID-19 among Mozambican adults, we study the interaction between a supply and a demand intervention, respectively: teaching via targeted feedback, and providing financial incentives to learners. In theory, teaching and learner-incentives may be substitutes (crowding out one another) or complements (enhancing one another). Experts surveyed in advance predicted a high degree of substitutability between the two treatments. In contrast, we find substantially more complementarity than experts predicted. Combining teaching and incentive treatments raises COVID-19 knowledge test scores by 0.5 standard deviations, though the standalone teaching treatment is the most cost-effective. The complementarity between teaching and incentives persists in the longer run, over nine months post-treatment.

- Keywords: COVID-19, Teaching, Education, Learning, Cost-effectiveness, Mozambique, Africa

- JEL Classifications: I10, I21, D90

-

Presentations: Northwestern University | Human Capital, History, Demography, & Development (H2D2), University of Michigan

- Pre-Analysis Plan: submitted to the American Economic Association’s RCT Registry on August 25, 2020, under registration ID number AEARCTR-0005862.

- Populated Pre-Analysis Plan (Populated PAP)

Project Details

This project is funded by the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) Innovation in Government Initiative through a grant from The Effective Altruism Global Health and Development Fund (grant number IGI-1366), the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office awarded through Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) Peace & Recovery Program (grant number MIT0019-X9), the Michigan Institute for Teaching and Research in Economics (MITRE) Ulmer Fund (grant number G024289), and the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.

This study’s protocols have been reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at the University of Michigan (Health Sciences and Social and Behavioral Sciences IRB, approval number HUM00191506) and the Mozambique Ministry of Health National Committee on Bioethics for Health (Portuguese acronym CNBS, reference number 302/CNBS/20). The study was submitted to the American Economic Association’s RCT Registry on March 8, 2019, registration ID number AEARCTR-0005862: https://doi.org/10.1257/rct.5862-1.0.

COVID-19 Survey Timeline

Policy Briefs

Round 1 Survey

Round 2 Survey

Round 3 Survey

Round 4 Survey

Have any questions?